Table of contents

Skip table of contentsIf you want to be kept up to date with new articles, CSS resources and tools, join our newsletter.

When people talk about CSS complexity, a major contributor to that is CSS specificity, or writing effective CSS selectors. The more you add to a CSS selector, the more precise it is, but also, the more specific it is, so the harder it will be to overwrite styles if you need to at a later point.

This double edged sword is what makes writing good CSS selectors so hard: you need to be specific, but not too specific. It's why there are many strategies for writing good CSS selectors or avoiding the issue altogether, from OOCSS to BEM to Atomic CSS.

This article is adapted from a talk Kilian gave at Web Directions Hover 2022. You can contact us if you're interested in Kilian presenting this at your conference, meetup or organisation.

CSS is quickly evolving at the language and syntax level. Container queries and cascade layers for example will each have their impact on the selectors you will write in CSS. Cascade layers are widely available, and you can test with Container queries right in Polypane.

In this article though, we're not going to focus on the syntax, but we're going to focus in on some new features that are available for the CSS selectors: the :is(), :where() and :has() pseudo-classes. Yes, I flipped them in the article title because they sound more fun that way.

A bit of history

Before there was the :is() pseudo-class, there was the :matches() pseudo-class. And before that there where the *-any pseudo-classes: :-moz-any() and :-webkit-any().

You might be surprised to learn that the *-any pseudo-class has been around since 2010. It was introduced in Firefox 4 as :-moz-any(), outside of any specification, and actually worked pretty much the same as the :is() class works now.

Support in other browsers landed first as :-webkit-any(), and later it got added to the specification as :matches(), which also had support in various browsers.

This :matches() pseudo-class came with a limitation though, like the :not() selector, it only supported "simple selectors".

What are simple selectors?

Simple selectors are selectors that only contain a single element or element property, like a class, attribute, id or pseudo-class. As soon as you add a combinator, like a space or ~ or +, or a pseudo-element (like ::first-letter or ::after), you add a relation to another element and it becomes a complex selector.

The definition of "simple selector" changed between CSS2 and CSS3: in CSS3 there is now a difference between a "simple selector", which is one thing (one class, one element, etc) and a compound selector, which is any selector that does not have a combinator.

That means that this CSS Selector is "simple" (though compound) :

p.hover#22[chat~=active]:focusand this one is "complex":

div pThis obviously put a limit on how useful both the :matches() and :not() selectors were, so luckily both of those got updated in later specifications and they now also support complex selectors, meaning we can use them to select elements based on their relations.

And that's not the only thing the :not() selector contributed to this history. The CSS Working group renamed :matches() to :is() because, for one, it was shorter to type, but it also provided a good pairing with :not().

Is, and is not.

Checking for support for :is()

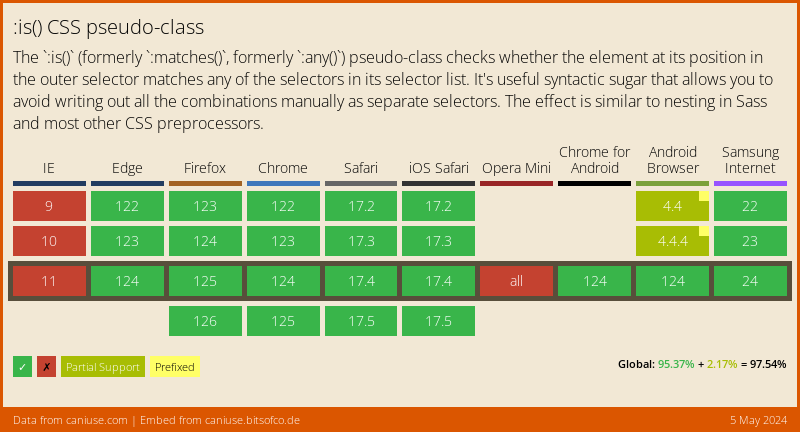

That brings us to the now, 2022. The :is() pseudo-class is supported in all evergreen browsers, with support only missing in IE11 and Opera mini.

If you want to test for support you can use the @supports rule with the selector() function, which has been supported for slightly longer than :is() itself and works for all three pseudo-classes we're discussing in this article:

@supports selector(:is(*)) {

/* your CSS */

}The :is() pseudo-class

To target multiple paths in CSS, you can add a comma between multiple selectors. Each selector will then be used to select elements.

nav > ul a:hover,

footer > ol a:hover,

aside > p a:hover {

color: purple;

text-decoration: underline wavy deeppink;

}This is useful but for closely related selectors it usually leads to duplication. specifically, the a:hover part is the same in each of the selectors.

This is annoying since if that ever changes, you have to fix that in three places at the same time, but there is something trickier going on with multiple selectors as well: if one of them is invalid, the entire block of CSS is discarded.

Now you might think that it'd be pretty hard to write a selector that's invalid. Maybe one that never applies, like :not(*), but an actual invalid one?

Well, consider new CSS pseudo-states that are only supported in some browsers, like :fullscreen (Safari only supports :-webkit-full-screen):

:fullscreen,

:-webkit-full-screen {

background: red;

}To style a fullscreen element in Chrome and Firefox you need :fullscreen, but in Safari you need :-webkit-full-screen. If you put those together then Firefox will see the :-webkit-full-screen selector, deem it invalid and discard the entire thing, and likewise Safari will see :fullscreen and discard it as well.

To style this in both browsers in a way that doesn't break, you would have to create two separate rule sets and duplicate the styling in both blocks. More duplication!

:fullscreen {

background: red;

}

:-webkit-full-screen {

background: red;

}That means selector lists have two problems:

- Duplication in the selectors you write, making updating them frustrating.

- If one of the selectors is invalid, everything is ignored.

Enter :is()

Solving both these issues with a single two-letter pseudo-class.

Firstly, the duplication, instead of creating a separate selector for each variant here, We can rewrite it to create mini selectors with the :is() pseudo-class, and then we only have to write the rest of the selector once:

:is(nav > ul, footer > ol, aside > p) a:hover {

color: purple;

text-decoration: underline wavy deeppink;

}Do you see how we essentially create a smaller list of selectors inside the :is()? By inlining the parts of the selectors that are different, we can make the entire selector much smaller and more readable.

And the :is() pseudo-class solves the second issue by creating a new type of list of selectors: the <forgiving-selector-list>. This will parse each selector individually and discard the ones it doesn't understand.

This means we can wrap our slider track pseudo classes in an :is() and browsers will just pick the ones they understand and ignore the rest:

:is(:fullscreen, :-webkit-full-screen) {

...

}That's great! The :is() selector saves us typing the same thing in multiple selectors, and also makes our CSS more resilient by introducing a forgiving selector list.

Filtering elements by their parents

A cool feature I learned from Stephanie Eckles in her Modern CSS Toolkit presentation (you can find the tips mentioned there on SmolCSS too). Because the :is() pseudo-class can take complex selectors, you can also add a list of ancestors and then select your element with a *. That means these two selectors target the same element:

a:is(nav *) {

...

}

nav a {

...

}This works because the browser will look for all elements that match both a and that match nav *. The end result being that you're actually selecting nav a, the a element matching both a and *.

Nesting pseudo-classes

Another consequence of complex selectors being supported, is that you can nest pseudo classes:

:is(div:not(.demo) nav) {

...

}What this selector selects is:

- All

navelements, - That are in a

div, - But only if that

divdoes not have a class of "demo".

About :not()...

:not() will break if it contains invalid selectors because the specification states it should use a "regular" selector list, not a "forgiving" selector list like :is().

The workaround for that is to nest an :is() selector in your :not() selector, though it would be better if the specification got updated so that the not selector also uses a forgiving selector list.

/* breaks */

not(:fullscreen, :-webkit-full-screen) {

...

}

/* works */

not(:is(:fullscreen, :-webkit-full-screen)) {

...

}Things to look out for with :is()

The :is() pseudo-class itself also comes with a few gotchas:

No support for pseudo-elements

You can not select pseudo-elements like ::before and ::after, since they aren't elements present in the DOM and so can't "match".

/* won't work */

a:is(::before, ::after) {

...

}

/* You have to write */

a::before,

a::after {

...

}Spaces are significant

The space is part of the selector, so you have to keep that in mind.

h1:is(:hover, :focus) {

...

}

/* h1:hover, h1:focus { ... } */

h1 :is(:hover, :focus) {

...

}

/* h1 *:hover, h1 *:focus { ... } */In the above example, the top line h1:is(:hover, :focus) will evaluate to the hover and focus applying to the h1 but adding a space between the h1 and the is selector evaluates to the hover and focus applying to any descendant. The universal selector (*) is added implicitly.

Specificity

Everybody's favorite CSS topic, and :is() does something interesting with it.

Specificity in selectors is expressed as three numbers: the first is for IDs, the second for classes and pseudo-classes and the third for elements and pseudo-elements. Any number will prevail over the ones after it, so you can have a hundred classes and still a single ID would win in terms of specificity.

#id= (1,0,0).class= (0,1,0)div= (0,0,1)

If you want to explore this for yourself, We made an online specificity calculator that visually explains which parts your selector is built up from and explains the scoring.

To determine the specificity of an :is() selector, browsers don't just take the default value of a pseudo-class (0,1,0), but they take the value of the most specific selector in the is pseudo-class. This means you can easily blow out your specificity without paying attention to it.

/* regular pseudo-class */

:first-child {

} /* (0,1,0) */

/* :is pseudo-class */

:is(h1, ul.nav, #message) {

} /* (1,0,0) */The specificity of that second example ends up being (1,0,0) because of that one ID selector, even if that selector doesnt actually match any element in your DOM.

The most specific selector determines the specificity.

What if there's no way around using a high-specificity selector? That brings us to the next pseudo class on our list.

The :where() pseudo-class

:where() was introduced a little later but is now as well supported as the is() selector: all evergreen browsers, but no support in IE11 or Opera mini.

It was created to solve this issue of specificity. It works exactly the same as the :is() pseudo class with one key difference: its specificity will always resolve to (0,0,0), regardless of the selectors inside it.

:where(div) /* (0,0,0) */

:where(.class) /* (0,0,0) */

:where(#id) /* (0,0,0) */This can help you escape out of issues where your only recourse would've been an even more specific selector or adding an !important to a CSS rule.

While useful for specificity issues, there is another area where I think the :where() pseudo class will hopefully make a big impact: in CSS libraries and resets.

A simpler alternative for cascade layers

With the :where() pseudo class, libraries can ship their styling with zero specificity. You get all the benefits of a library without having to deal with specificity to overwrite its styling. Open Props is a CSS Library that already applies this pattern.

While cascade layers may be getting more attention lately as a potential solution for the same problem of specificity and CSS frameworks, I think the effectiveness of :where() should not be underestimated. `:where() can be applied at a selector level, and doesn't require you to change and keep in mind your entire CSS architecture in the way cascade layers do.

So that's :is() and :where(). These two pseudo classes help us cut down on selector duplication, are forgiving when it comes to invalid selectors, something that can be particularly helpful in cross-browser support and in the case of :where(), help us manage the specificity of a selector.

Both :is() and :where() are supported in all evergreen browsers and have been for quite a few versions, so they are safe to use if you no longer have to support Internet Explorer, which I hope you don't.

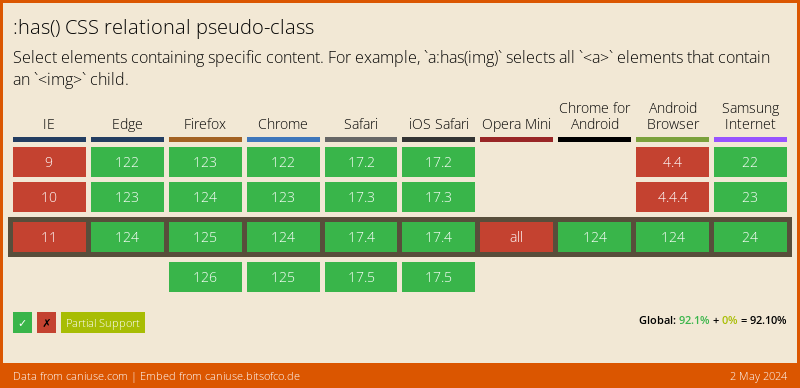

That brings us to the last pseudo-class of this article. It's the newest and most unsupported one, but it's one that developers have been asking for since, well, since forever:

The :has() pseudo-class: the parent selector.

Let me explain "parent selector" a little bit. With CSS selectors you already style elements by their parents, but what people mean when they say a parent selector is that they want to style an element based on what other elements are inside of it. For example, they want to say something like this:

/* ↓ Select this */

this(div) img

/* ↑ not this */to specify they want to select divs, but only if they contain images.

While there have been many proposals over the years, this was long thought impossible or too performance-intensive to implement because of the way CSS selectors are parsed: they start at the end.

/* Starts here ↓ */

header h1#sitetitle > .logo a { }

/* ↑ Not here */They are parsed this way because browsers start with the element and try and find all the CSS that applies to it.

It's faster to invalidate rules that don't apply to a given element when you start at the end of a selector, because you don't have to loop over all potential descendants only to find out that the element at the end doesn't match.

By starting at the end, you can begin by discarding all elements that are not a elements (in this case). That lowers the total number of elements you will need to consider. From there, you can walk up the tree one ancestor at a time to discard any further non-matching elements.

While some veterans might now have flashbacks to old arguments about performance, jQuery plugins and the like, it's 2022 and the :has() pseudo-class lets us select elements depending on their descendants, natively in the browser, without any noticeable performance implications.

So first the bad news:

Browser support

The :has() selector is available in Safari, in Polypane and in other Chromium browsers. It's available behind a feature flag in Firefox.

When I said that there are no performance implications, what I meant was that there were no performance implications in Webkit and Blink. Each rendering engine has different optimizations, so the implementation in Firefox's gecko engine might end up having other performance characteristics.

Of course, that won't stop us from exploring its many possibilities, because like Bramus said, the CSS Has pseudo class is way more than a parent selector. In the specification it's referred to as the relational pseudo class, and we'll see why in a bit.

The syntax

First though, the syntax. To get back to the example I just gave, of selecting all divs that contain an image, here's what that looks like with :has(). We select all the divs, but add a conditional that they need to have images inside them.

/* ↓ Select this */

div:has(img);

/* ↑ not this */Like :is() and :where(), you can also use complex selectors. Like divs that have images as siblings.

div:has(~ img) {

...

}or multiple selectors, like divs that have images, videos or svgs as descendants.

div:has(img, video, svg) {

...

}Also like :is() and :where() the selector list is forgiving. So div:has(img, video, svg:undefined), with a ":undefined" pseudo that doesn't exist, will still select all divs that have images or video elements in them.

As of late 2022,

:has()no longer has a forgiving selector list, due to that breaking jQuery. If you need a forgiving selector list, then you can nest:is()or:where()inside it:div:has(:is(img, video, svg:undefined)).

Specificity

The specificity of a :has pseudo class is determined in the same way as for the :is() and :not() pseudo-classes: the most specific element determines the specificity of the entire pseudo-class.

div:has(img, .logo, #brand) /* (1,0,0) */Using :has() as part of a selector

By using :has() in different parts of your selector you can not just select elements based on their descendants, but also select elements based on their sibling or even cousin elements.

Or in other words, we can select elements based on their relation to a different part of the DOM: the relational pseudo class.

For example, lets say you have a card element and you want to style the h3 differently if the card image is present:

<div class="card">

<div class="imagecontainer">

<img src="" alt="" />

</div>

<div class="textcontainer">

<h3>Title</h3>

<p>...</p>

</div>

</div>We can do that by making :has() part of the selector that targets that h3. To target the h3 we'd normally write .card h3. Next, we add a conditional :has() to the card:

.card:has(.imagecontainer img) h3 {

...

}This selector matches:

- All h3 elements,

- That are in elements with the class card,

- But only if that card element also has:

- An image

- In an element with the class imagecontainer.

We can also invert that: style the h3 differently if there is no image present, by nesting a `:not() pseudo-class.

.card:has(:not(.imagecontainer img)) h3 {

...

}This gives you a lot more styling options for situations where you would've previously added something like class="has_image" to your card.

Re-implementing :focus-within

You can also use :has() to implement :focus-within, which lets you target element if any of their descendants have focus. Both of these act the same:

form:focus-within {

...

}

form:has(*:focus) {

...

}Though with :has() we can go one step further, like only styling the form if it's a specific element that has focus. This is not possible with focus-within:

form:has(input[type='radio']:focus) {

...

}Showing an "other" input field without JS

It works for other pseudos as well, like :checked. With this we can implement an "other" input field that appears when a specific option is checked without writing a single line of JS:

form:has(input.my-checkbox:checker) input.my-textfield {

display: block;

}Styling forms if they have errors

You can also pull up things like the :valid, :invalid and :user-invalid pseudo-classes to style a form differently:

form:has(input:user-invalid) {

border: 3px dashed red;

}Or even to show a list of invalid or missing form fields at the top or bottom of the form:

form:has(.name:user-invalid) li.name-warning {

display: block;

}There are many more examples you can think of, but I hope this has given you a good idea of the potential the :has() pseudo-class brings.

The future for CSS selectors

I very much look forward to all the clever things people will come up with using :is(), :where() and :has(), and don't think the examples above even scratches the surface.

Especially :has() is going to have a very large impage on the CSS selectors you will be writing in the coming years.

If you want to play around with the :has() selector ahead of general availability, you can start a free Polypane trial which has it enabled by default.